We’ve all seen them. Maybe you’ll still find one sitting in your own Instagram profile. That one post of just a sole, black square. Perhaps you captioned it “#blackouttuesday.” Or it might even say “#blacklivesmatter” under it. But whatever words rested beneath that black square, you knew that your late-night post on June 2, 2020, served as your memorializing pin that told the entire world (or well, at least your Instagram followers) that you are an activist.

Because that’s how activism works…right?

It’s time we talked about the links between performativity and activism.

To truly understand the complex relationship between these two phenomena, we must first lend our attention to what “popularized” activism in the first place. In late-May, last summer, protests around the nation began after the horrendous killing of George Floyd. With this came the resurgence of #BlackLivesMatter, a global organization “whose mission is to eradicate white supremacy and build local power to intervene in violence inflicted on Black communities by the state and vigilantes.” During that summer, the attention that was brought to the Black Lives Matter movement was greater than ever before. This national call-to-action has been attributed to the changes that have been made in regards to how we now interact with each other (changes that have only been exacerbated since the onset of the wildly mishandled COVID-19 pandemic).

What I’m referring to is our relegation to the virtual.

Instead of relying on the pamphlets, flyers, and word-of-mouth methods used during the Civil Rights Movement, community organizing now takes place with the immediacy and virality of the internet. As a result, people can now respond immediately to a piece of information—it only takes a few clicks to repost on your Instagram story, retweet a note out to your followers, or relay a message to your friends and family via text.

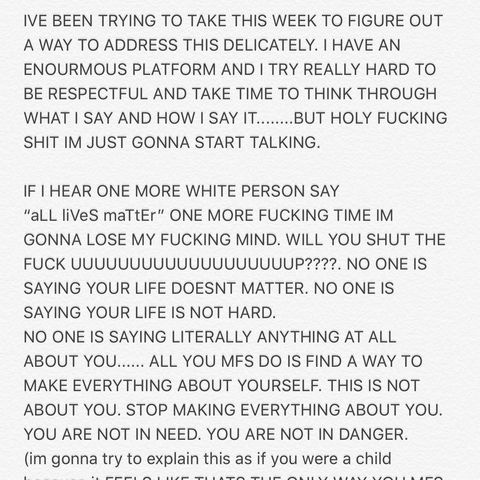

Amidst all of the much-needed attention that made its way towards the Black Lives Matter movement, however, came other expectations. Social media users began noticing who was posting about Black Lives Matter, and who wasn’t. This activism—or more accurately, the lack thereof—was made most apparent with the many white celebrities who, despite having the largest platforms capable of the greatest mobilization, chose to stay silent until they were called out by fans.

In the fast-paced environment of the internet, this lethargic meandering towards enlightenment that celebs reluctantly acted with made many fans, especially Black fans, wonder if they should continue supporting these influencers. What is the point of the “influencer” label, if these very influencers aren’t motivating their followers towards the right objectives?

This concept of “influencer status” has evolved in recent times. Even as early as 2016, social media had demonstrated its propensity towards making everyone an influencer. Have a social media account? Check. Followers that are influenced by your posts and shares, and by extension, your opinions? Check. That’s all you need in this day and age of high visibility to call yourself an influencer. And with sensations like Addison Rae and Charli D’Amelio, it only takes a few more of that second point until that check turns blue (no talent necessary!). This slippery slope of influencer vs “regular social media user”—if that even exists anymore—is exactly what caused people to start calling out more than their white celebrity idols; next in line was their friends who also stood silent in the face of injustice. Suddenly, if you weren’t using your platform to speak on issues at hand, you were giving followers room for suspicion. In comes a constant need to virtue signal on the internet, just to prove that you’re not one of them who’s in the wrong.

Think of the Tiktokker Eileen Huang (@bobacommie), who was called out for her video that attempted to expose fellow Tiktokker Nina Lin (@n.nina666) for her apparent appropriation of what Huang interpreted as African American Vernacular English. Many of Lin’s fans called Huang a “boba liberal,” due to her critiques of other Asian Americans.

They understood Huang’s video as a means to prove and perform her wokeness in regards to Black culture, via her virtue signaling of points already discussed by Black creators who previously pointed out this potential issue of cultural appropriation. On the other hand, supporters of Huang argued otherwise, stating that Lin was performing a culture that wasn’t hers in order to gain clout. No matter who was “right” in this situation, the narratives and theories that surrounded Huang and Lin are stark representations of one of boba liberalism’s greatest (worst) hallmarks—performativity.

“[Boba Liberalism] is all sugar, no substance… It’s about being solely focused on representation in media and politics; it’s about viewing our collegiate Asian student organizations as the vanguard of progress for our communities. Boba liberalism gave us Andrew Yang, who used model minority jokes as a campaign strategy.”

— Sarah Mae Dizon

“Why I Hate Subtle Asian Traits”

Performativity is a method of curating your image in a way that drives your audience (i.e., friends and Twitter moots) to believe a particular, glorified image of yourself. It’s retweeting a thread about anti-Blackness, without having read it yourself, just to show people that you’re not a racist. It’s showing up to your next Zoom meeting with a script about how you have “checked on all your Black friends” because of the hard times, despite doing nothing of the sort. And it’s posting a black square on a Tuesday night and nothing else, thinking you did something. If only I could type out an eye roll on paper.

This isn’t to say we should absolve ourselves from activism entirely. Rather, I’m proposing that when we do decide to activate, that we do so with authenticity and purpose. Speak on Black issues because they’re important, and important to you—NOT because you want to look “cool” or “woke.” The latter would be the empty transaction of Black bodies and voices, in exchange for clout. Educate yourself, before you pretend you have the capacity to educate others. Masquerading otherwise would mean the commodification of Black politics and activism, divorcing it from the true gravity that it should be given in order to mobilize all of our communities toward liberation. If anti-Blackness is your concern, then let’s not make light of Blackness by posting activism for the community without true intention. That, frankly, would be anti-Black.

In the words of Goddess Lula Belle from Solange Knowles’s latest album: “Nothing without intention. Do nothing without intention.”

What are some of your thoughts on performative activism and boba liberalism? Have you noticed its tendencies towards anti-Blackness in your own experiences? Feel free to share this with a friend and spark some important conversations.

Thanks for the read, and I’ll see you in the comments!

Instead of our regular list of follow-up readings, this time we’ll be recommending you to check out my collab with Incoming! Editor-in-Chief, Jordyn Paul-Slater. Listen to the podcast here.

If you liked what you read, be sure to subscribe and follow us on Twitter and Instagram @invisibleasians to stay updated on Politically Invisible Asians!

Such an important topic, a much needed piece to spark conversation! So impressed with this, Jalen ☺️

Great read, Jalen! I want to echo your sentiment by highlighting one of the frustrating forms of performative activism you noted: story reposts.

I go through story after story after story of people sharing posts that are meant to 'educate' or 'inform' their followers, but I often find myself asking if the person reposting it ACTUALLY took the time to go beyond the headline and look into the actual evidence and information they praise for being so enlightening. This has led me to be more cognizant of what I share. I refuse to repost a post simply because I want people to think I am educating myself. If I did NOT go through the post or article referenced in the post, then I will NOT share it.

Activism isn't just trying to educate and empower others. It's educating and empowering yourself first and foremost.