On October 24, 1871, a group of five hundred men ransacked California’s Old Chinatown, Los Angeles, killing 19 Chinese immigrants—most executed by hanging.

On March 3, 1875, the 43rd Congress of the United States enacted the Page Act, which barred Chinese women from entering the United States by classifying them as “lewd or immoral”—essentially labeling them as prostitutes.

On May 6, 1882, the 47th Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which barred Chinese people from entering the United States for the next ten years. In 1892, the 52nd Congress passed the Geary Act, which extended this ban for the next decade.

On May 26, 1924, the 68th Congress passed the Johnson-Reed Act, preventing immigration from Asia and setting immigration quotas for the rest of the world.

On August 3, 1979, a group of Ku Klux Klan-backed white fishermen firebombed several Vietnamese fishing boats and homes in Seadrift, Texas.

On June 19, 1982, a pair of white men murdered Vincent Chin in Highland Park, Michigan, because they thought he was Japanese.

And on March 6, 2021, a 21-year-old white man opened fire on three separate spas in Atlanta, Georgia, killing eight people, six of which were Asian.

Let me make it clear: we Asian Americans are not “basically white” or “white-proximal.” We are perpetual foreigners, subject to the ravages of whiteness in the same ways that many of our brothers and sisters of other races have been. If it took us being gunned down in our homes and businesses to recognize that, then history must not have imparted on America the lessons of our past. We’ve not seen our struggles in our history textbooks or class curriculums, so perhaps now is the time to realize that despite our “model minority” status, we’ve had a target painted on our backs from day one.

Some of those who did not grow up with “yellow skin” and “slanted eyes” think that the recent rise in anti-Asian hate crimes is an artifact of Trump’s rhetoric and the pandemic, destined to fade away with a new administration. But for Asian Americans, our reality is very different. What COVID-19 exposed was the sleeping, rabid dog hiding underneath veneers of pleasantry. Despite our best efforts to live as their neighbors, speak their language, and share in their American Dream, white society would always see us as something Other, something detestable.

This recent wave of anti-Asian hate is simply business as usual. Don’t forget that we died building your railroads just to turn around and endure one of the worst immigration acts in modern history. Don’t forget that we crossed the ocean for the promise of gold, like white people, just to be pushed out. And most of all, don’t forget that kids like me saw how you treated us—the names you called us, the looks you shot at us, the way you pulled your eyes and mimicked our accents. Asian Americans have been put down, abused, and murdered on the basis of our skin color since we first stepped foot on these shores. Our stories, however, have been muffled because we “behave.” We can’t suffer under whiteness because we’re “basically white,” right?

But we can, and we do. Take Vincent Chin, for example, someone that the Asian American community has never forgotten but the rest of America seems to have. On June 19, 1982, Vincent Chin was celebrating his upcoming wedding when he was brutally beaten to death by two white auto-workers. Chin’s murder—explored in the 1987 documentary film Who Killed Vincent Chin?—was an outpouring of xenophobic, racial hatred, all because his killers believed that he was Japanese. At the time, the astronomical rise of the Japanese auto industry was pushing many American auto-workers out of work (his killers included). Chin’s murderers were later sentenced to three years’ probation and a fine of $3,000, a slap on the wrist that has echoed throughout the Asian American community to this day.

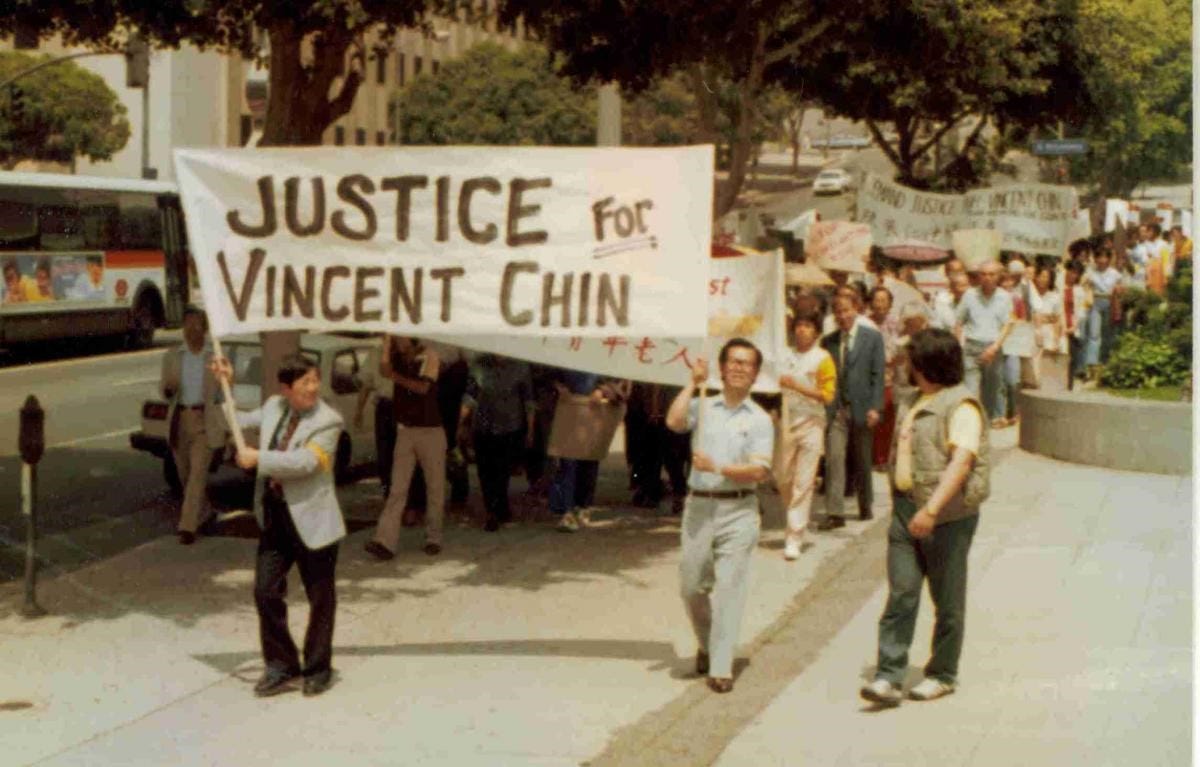

After the lenient sentencing, the Asian American community erupted in outrage, a moment widely considered a turning point for Asian American civil rights engagement. Activist Helen Zia led a group of American lawyers and community leaders to form American Citizens for Justice, an organization that partnered with churches, synagogues, and Black activists to protest the sentencing. People began to hold their own demonstrations across the country. At the end of the day, however, despite the widespread galvanization of Asian Americans across the country, little changed. Neither of Chin’s killers saw a single day in jail.

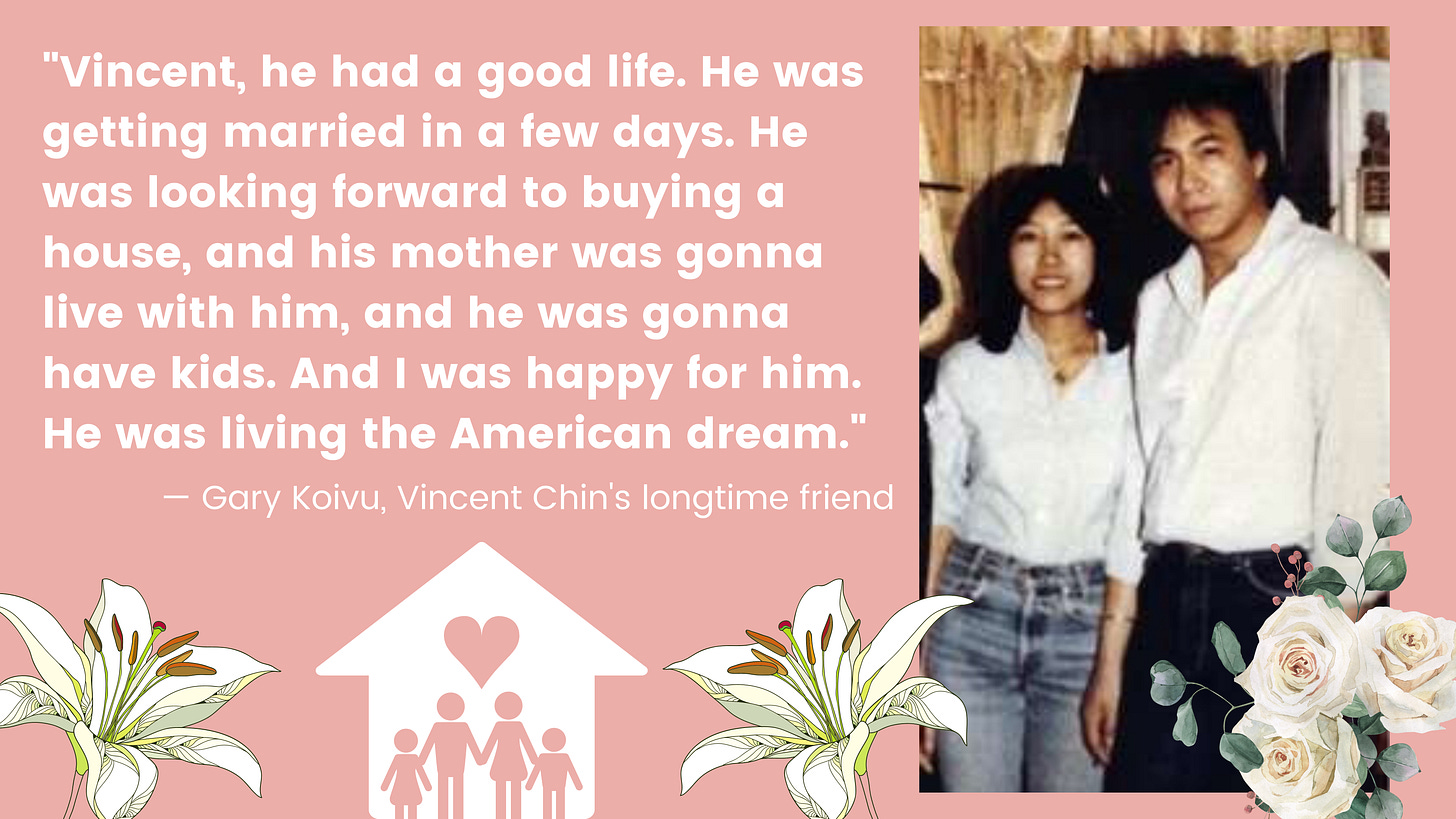

But we can’t forget that Vincent Chin was a man with his own hopes and dreams, not simply a victim of racial violence. Born into a Chinese orphanage on May 18, 1955, he was adopted by a World War II veteran, Bing Hing Chin, and his wife, Lily. Chin spent much of his life in Highland Park, Michigan; despite being born in Guangdong, he was just as American as they came. Gary Koivu, his longtime friend who was to be Chin’s best man at his wedding, remembered this about him:

Like it or not, Vincent Chin’s murder proves a number of things. Firstly, though it’s been a running gag for years and decades, white people cannot tell Chinese Americans apart from our Asian American brethren. “You all look the same!” they tell us. Where it was once just a jab at our appearances, Chin’s murder exposed the ugly consequences of this anti-Asian rhetoric. In the case of Vincent Chin, hatred for the Japanese led to a Chinese death. Now, hatred for China is killing all Asian Americans simply for “looking the same.” Despite how well we seem to do—and truly, we are not doing well at all—we will always be seen as something alien and non-native.

Our identity is perpetually and externally determined by white power; where white people are free to choose for themselves what they will become and transcend racial boundaries, the same cannot be said for us. The power afforded to whiteness is precisely what makes life in America so precarious. They can characterize and shape our identities, grant and take away our wretched “model minority” status, and even strip away our right to live. From 1871 to today, Asian Americans have earned what we believed to be a begrudging acceptance from whiteness to live our lives, own our businesses, and nurture our communities. But the Chinese Massacre, the Chinese Exclusion Act, Vincent Chin, COVID-19, and now Atlanta have shown us that this superficial “most preferred minority” status can always, without exception, be taken away. I urge the Asian American community to recognize this reality. No matter how far we think we’ve gotten, we must remember that we will always be perceived as strangers in this land, and that we have always been susceptible to the murderous power of American racism.

We have never been invulnerable. To protect ourselves, we must first come to grips with the ever-present reality that there will always be something stopping us from being American, and leaving us perpetually Asian American. But at the same time, we should be careful not to disavow our heritage—after all, it is what ties us to our homelands, and gives us our identities.

To further decolonize our minds:

Scott Kurashige | Detroit and the Legacy of Vincent Chin

Mark Tseng-Putterman | On Vincent Chin and the Kind Of Men You Send to Jail

NBC Asian America | Voices: Who Is Vincent Chin?

If you liked what you read, be sure to subscribe and follow us on Twitter and Instagram @invisibleasians to stay updated on Politically Invisible Asians!

Very important!

🗣Let me make it clear: we Asian Americans are not “basically white” or “white-proximal.” We are perpetual foreigners, subject to the ravages of whiteness in the same ways that many of our brothers and sisters of other races have been.