I grew up in Queens, New York, in a predominantly white neighborhood, with just a handful of Chinese families scattered here and there. I used to live blocks away from Panda, a family-owned Chinese takeout spot. On the days when my parents would come home from work completely exhausted, we would order the most amazing beef with broccoli from that dimly lit restaurant. Their beef with broccoli comforted me throughout my life—from elementary school, to my first, nerve-racking day in high school, and even to university days after an exhausting and difficult exam. It was the meal I missed a lot during the years I went to Buffalo for university.

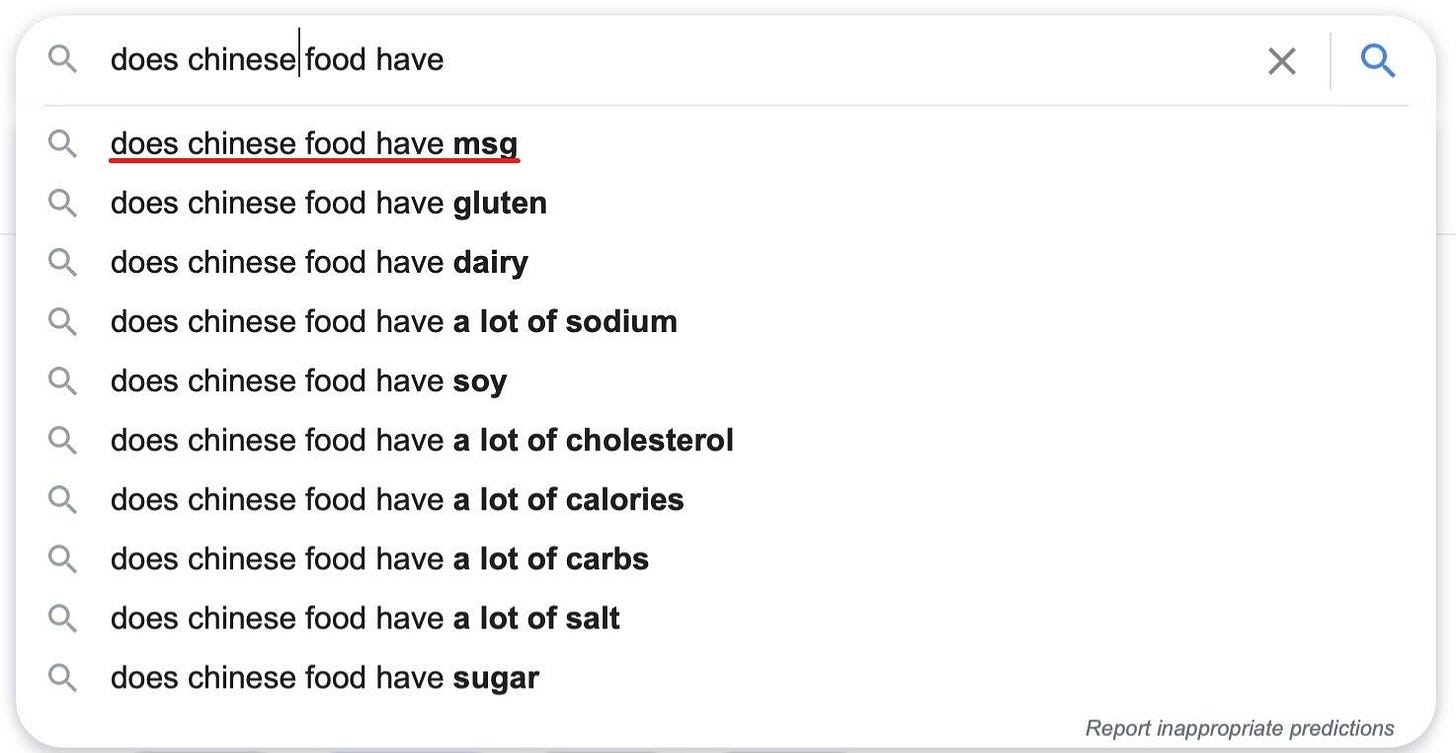

Ever since I moved to Manhattan, I noticed there were “no MSG” signs plastered on every single Chinese takeout menu. Where was this message on the menu of other cuisines? It seemed as if the survival of Chinese restaurants depended heavily on the fact that they didn’t use MSG. But, is this savory, umami-yielding substance really that harmful?

MSG Debunked

According to the Food and Drug Administration’s website, Monosodium glutamate, more commonly known as MSG, is safe to consume. In truth, MSG occurs naturally in a variety of foods, including anchovies, oysters, egg yolks, walnuts, mushrooms, corn, tomatoes, cheeses, and marmite, just to name a few common ingredients.

The year 1908 marked a revolutionary emergence in the food industry, when Kikunae Ikeda, a Japanese professor, isolated MSG from a concentrated seaweed broth. As a result, this powdery umami substance can be added to any dish! Like salt, MSG is a popular additive to food since it enhances a recipe’s flavor. By the 1950s, MSG had become a major success and was widely accepted in American kitchens. Today, the seemingly controversial ingredient is even incorporated into recipes of top food brands like Chick-Fil-A, KFC, Doritos, and Campbell’s chicken noodle soup, just to name a few.

If the major brands have incorporated this ingredient into their recipes, why does American society still think of MSG as harmful? To properly understand the MSG debate, we have to rewind and look at the history of Chinese Americans.

In 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act became the first and only legislation in America to ban immigrants from a specific country. It wasn’t until 1965 that this ban was completely repealed. Replaced by the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, it was illegal for the government to discriminate against people of natural origin, thus leading to an influx of Asian immigrants who desired an education and a chance for work in the States. Most of the Asian immigrants that arrived after the Act of 1965 came for job opportunities that sought highly skilled workers. In the mid-1960s, the model minority myth began entering Asian American discourse after sociologist William Petersen published an article in the New York Times glorifying Japanese American immigration stories, which ultimately drove a wedge between Asians and other minority groups.

Around the same time, in 1968, Dr. Robert Ho Man Kwok sent a letter titled “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome” to the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), where he discussed the symptoms of eating at a “Chinese” restaurant.

“For several years since I have been in this country, I have experienced a strange syndrome whenever I have eaten out in a Chinese restaurant...Numbness in the back of the neck, gradually radiating to both arms and the back, general weakness, and palpitation.”

— Dr. Robert Ho Man Kwok

Do some slight research on MSG, and there’s no doubt that you’ll come across the name Dr. Robert Ho Man Kwok. What most people don’t know, however, is that “Dr. Robert Ho Man Kwok” was actually an alias for Dr. Howard Steel, the real doctor who wrote the letter. Although the surname Ho Man Kwok faintly alludes to a person of Asian descent, Dr. Howard Steel was a white male orthopedic surgeon. In the letter to NEJM, Dr. Steel kept linking his illnesses to Chinese food, misconstruing the relationship between the Chinese identity and illness.

Dr. Steel sent the letter as a comic syndrome letter, somehow never realizing that it would actually be published and taken seriously. In the end, he even tried to communicate to the NEJM that the letter was a joke, but it was to no avail. Regardless of his intentions, this doesn’t erase the fact that Chinese Restaurant Syndrome, now MSG Symptom Complex, is recognized as a xenophobic term that continues to harm Chinese food establishments to this very day—thus, the reason why we now see Chinese restaurants feel the pressure to put “no MSG” signs on their storefront windows over 50 years later.

A more current example can be pulled straight from the words of no other than our former president, Donald Trump. His inflammatory rhetoric linking the Chinese community with the origins of the COVID-19 virus echoes the past, racist actions of Dr. Steel. By popularizing the term “Chinese virus,” Trump has actively contributed to what is now a massive surge in anti-Asian hate crimes, jumping by 1,900 percent.

A Nation’s Palate

Ethnic cuisines are often pressured to tailor to a nation’s palate. For example, Sriracha in France is very mild when compared to its spiciness in other countries, as the majority of French citizens are not as accustomed to consuming spicy foods.

Take a look at McDonald’s, for instance. This American fast-food chain alters their menu depending on the country they are serving. In Japanese McDonald chains, they created “ginger fried pork” burgers to mimic the popular dish Pork Shogayaki. This phenomenon is a survival tactic businesses use to draw in customers from the local area.

American Chinese Cuisine

Although Chinese food is modified extensively to the American palate, the dimly-lit family-owned takeout places are still delicious! It’s a different kind of delicious, of course, but I will forever continue to support my local takeout places because I enjoy the unique flavor profile of American Chinese cuisine.

However, American Chinese cuisine becomes problematic when people reduce the entirety of authentic Chinese cuisine to particular dishes. One famous example is Panda Express, which is not even real Chinese food. In fact, these modified Chinese dishes will likely confuse a native Chinese person. Take the case of crab rangoons, an appetizer that doesn’t even exist in China.

When people are quick to dismiss Chinese cuisine due to a few bad experiences with particular dishes, misconceptions are created to the extent that they can lead to the defamation and demonization of Chinese cuisine and Chinese people.

Controversies Explained

In recent years, there have been controversies surrounding restaurants and chefs that play into the “dirty” and “unhealthy” Chinese food stereotypes previously promoted by individuals such as Dr. Steel and Donald Trump.

In April 2019, Lucky Lee’s faced backlash for marketing their food as “clean” Chinese food. They issued a half-hearted, business-focused apology on Instagram. The statement goes on to defend their own restaurant, rejecting accountability and seemingly writing it off as if they were allowed to have this exception. We must remember, racism in any context, anywhere cannot be tolerated.

“I never meant for the word “clean” to mean anything other than in the “clean-eating” philosophy, which caters towards a specific nutrition and wellness lifestyle. I also did not realize that the plays on words we used for marketing purposes were reminiscent of offensive language used against the Chinese American community.”

— Lucky Lee’s

View full apology here

In December 2020, "Masterchef: The Professionals'' contestant Philli Armitage-Mattin created the taglines “Dirty Food Refined” and “Asian Specialist” for her Instagram. The chef eventually made a statement about the incident, but many took it as a non-apology.

So Now What?

Support your local Chinese restaurants during this difficult time. Since January 2020, discriminatory COVID-19 fears in conjunction with harmful rhetoric instigated by Trump’s politically charged “Chinese virus” have harmed Chinese restaurants, leading to a decrease in business activity and business closure.

“In March 2020, restaurants in Chinatowns from San Francisco to New York reported as much as an 80% loss in foot traffic, triggering Chinese restaurant closures and accelerating what some have been warning about and fearing—a steady decline of historic Chinatown districts that won’t be able to fully recover when the pandemic subsides.”

Combat ignorance by learning about the wonderful world of Chinese cuisine, and trust me, it will take a long time just to get acquainted with them all, given how vast and expansive China is. To prevent any further harm to Chinese restaurants and Chinese Americans, we as Americans must actively educate ourselves to de-exoticize Chinese cuisine and authentically incorporate it into the melting pot that America claims to be.

How do you feel about American Chinese cuisine? Do you have a go-to order? No matter where you’re located, I’d love to hear your Chinese restaurant recommendations in the comments below!

To further decolonize our minds:

Shortcut from This American Life | Featuring Dr. Howard Steel

Mashed | The Surprising Origin of Chinese Takeout Boxes

TED | The Hunt for General Tso

Vice | Coronavirus Fears Are Reviving Racist Ideas About Chinese Food

Eater | The Limits of the Lunchbox Moment

Youtube | 7-Eleven Dim Sum Breakfast in Hong Kong

If you liked what you read, be sure to subscribe above and follow us on Twitter and Instagram @invisibleasians to stay updated on Politically Invisible Asians!

Amazing! but smh Dr. Steel

Super impressed with every piece you guys have put out