No, NPR’s Story on Michelle Wu’s Election Does Not Feed into the Trope of Black-Asian Conflict

Centering the Voices of Black Residents Who Wanted to See a Different Mayor Isn’t an Argument for Why She Shouldn’t Be in Office.

This past Election Day, many Asian Americans had cause to celebrate. In cities across the country, Asian Americans saw someone that looked like them rise to political office. Notably, Michelle Wu made national headlines as the first woman of color to be elected Boston mayor.

The daughter of Taiwanese immigrants, Wu was also the first Asian American woman to serve on the Boston City Council. The Boston Globe reports that she ran on an “unapologetic, progressive agenda.” She is seeking to, among other things, propose a version of the Green New Deal on the municipal level, eliminate transit fares, and reimplement rent control. She has a close relationship with Elizabeth Warren as the senator’s former law student, and Warren endorsed her for mayor.

But Wu is technically not the only woman of color to serve as Boston’s mayor. Kim Janey, a Black woman, stepped in as Acting Mayor for eight months after the incumbent left to work in President Biden’s administration. Janey made history when she became interim mayor; for the past 200 years, only white men have been mayor. She has publicly reflected on her path from a child bused into a white neighborhood in the 1970s to holding the city’s highest office.

After Wu’s win, NPR reported some Black voters expressed disappointment that Janey and other Black candidates, Andrea Campbell and John Barros, didn’t receive more votes, and that they would have yet to see Boston’s first Black mayor.

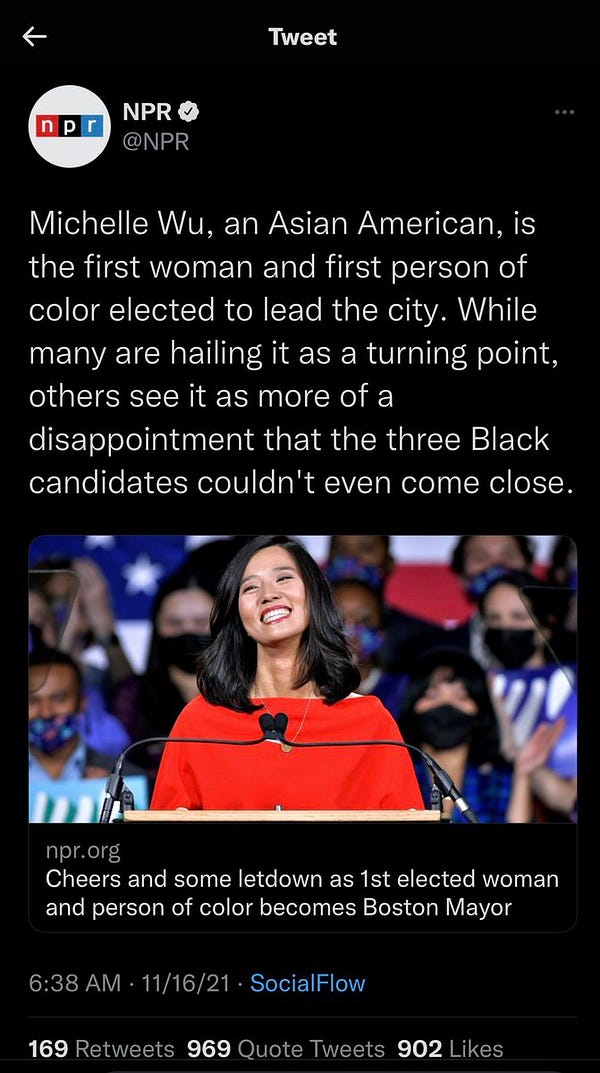

“While many are hailing [Wu’s election] as a major turning point, others see it as more of a disappointment that the three Black candidates in the race couldn't even come close,” NPR reporter Tovia Smith wrote.

Former Massachusetts State Rep. Marie St. Fleur pointed out that Boston still carries the reputation of being a racist city, and Black candidates only won a quarter of the votes in the whitest areas.

Fleur told NPR: "For those of us born or raised in Boston, and who lived through some of the darker days, the fact that we blinked at this moment is sadness," she says. "At what point in the city of Boston will we be able to vote — and I'm going to be very clear here — for a Black person in that corner office?"

The article’s original headline read “Cheers and some letdown as 1st elected woman and person of color becomes Boston Mayor.” On Twitter, NPR wrote that some Bostonians were disappointed that the three other Black candidates “couldn’t come close” to the number of Wu’s votes.

The headline, and the tweet publicizing the article, drew swift backlash on social media. NPR was accused of stoking racial division between Black and Asian communities, feeding into the trope that the two minority groups are constantly in conflict. There was a sense that NPR marred Wu’s historic win.

In response, NPR deleted its tweet and changed the headline of the article. The organization issued an apology for both, citing that the tweet caused harm.

Right-wing personalities and similarly aligned news media jumped on NPR’s retraction (and the story generally), accusing the public radio organization of being “race-obsessed.” Andrew Yang even made an appearance on Fox News to say the story diminished Wu’s victory.

"The fact is, there's a media fixation on race that ends up dividing people, pitting different groups against different groups," Yang told Fox News.

Concerned Asian Americans saw the story pitting two already-marginalized communities against each other. This fear is understandable at a time when racial solidarity feels fragile, yet is incredibly necessary.

But what I heard were the voices of people who were hoping their very white city would finally, finally have a mayor that cared about them. To the Black residents NPR interviewed, they were not content to see the mayoral role plugged in by anyone whose skin color wasn’t white. Therein of course lies the issue with a generalizing term like “women of color” or “people of color,” that tidily binds together the diverse experiences of oppression in America.

As some celebrated a win for representation, these Black residents and political organizers had something different to say. They had diverging hopes for the future of their city, but not once did they attribute Janey and other Black candidates’ loss to Wu or her race; to discredit NPR’s story as perpetuating Black-Asian conflict is to minimize these residents' sadness and concerns. We need to interrogate why we are so quick to dismiss a story that centers Black people’s reactions to a political outcome because it contradicts what makes us feel good.

Full disclosure, I formerly worked as NPR’s “Diversity Intern.” I left the role with mixed feelings about the efficacy and impact of such a position in an organization as massive and slow to change as NPR. I’m not here to say they have a flawless track record on race reporting. But in the hubbub of outrage, the sentiments of these Bostonians are being lost. So is another key point – that these voters intend to hold Wu accountable to the Black community.

At Janey’s farewell address, NPR reported that Wu said: "I have heard and want to continue acknowledging the disappointment of many in our community who wish to see representatives of the Black community. We will continue working to meet this moment to take on systemic racism and the barriers that have been perpetuated for far too long."

Further, NPR’s apology and retraction of the tweet seemed more like damage control than genuine contrition. The maligned tweet was taken from the article nearly word-for-word; if the tweet caused harm, the article must magnify this impact, but it remains without even a correction. It appears that the organization’s objective was to maneuver out of a social media crisis in the most painless way, rather than engaging in good faith with the central criticism of the story’s framing.

I do have issues with the story, unrelated to whether or not it feeds into the conflict trope. It lacked critical analysis of systemic factors that may have hindered Black candidates; the people NPR interviewed seemed to imply that it was because not enough Black voters backed one candidate. I want to know what kinds of state or city-implemented political hurdles make it harder for Black people to vote. I want to know if anti-Black rhetoric emerged on the campaign trail. Systems of white supremacy – predicated on theft of labor from Black people and land from Indigenous people – continue churning, even in the background of a supposedly racially progressive victory.

It’s true that the Black-Asian conflict trope is an erroneous generalization that continues to affect our communities. Along with the Model Minority Myth, this stereotype obscures America's colonial and imperialist history. The mainstream news media plays a central role in perpetuating it. We observed this in real-time as broadcast news played footage of Asian people being attacked, with the perpetrator always Black or brown, again and again – never mind that three-quarters of offenders in anti-Asian hate crimes and incidents are white, as American Studies professor Janelle Wong found.

The Black-Asian conflict trope has roots in the 1992 Los Angeles Riots, when residents responded to the acquittal of four police officers who were videotaped brutally beating Rodney King. In Koreatown, rioting resulted in immigrant stores being looted and damaged. You may have seen the infamous photo of the “Rooftop Koreans,” showing Korean men armed with guns to presumably protect their businesses from rioters; these photos were popularly interpreted as a “stand your ground” type action that marked the men as “heroes.”

University of Wisconsin-Madison professors Michael Thornton and Hemant Shah analyzed magazine coverage of Black-Asian relations during the decade before the riots and the year it happened. Their paper, published in 1996, found that 3 out of 4 articles studied “note tension or an unsettling incident between groups.” Over 60% featured fear and violence.

Korean residents in L.A. took up arms during the riots of 1992, after four police officers who brutally beat Rodney King were acquitted of excessive force charges.

The news media portrayed the 1992 riots as a struggle between racial minorities, with Black people framed as violent rioters and Koreans as victims. In addition to being racist, what this narrative leaves out is the culpability of the LAPD in destruction of businesses because the police virtually abandoned their Korean residents. It also omits the shared sense of injustice some Koreans felt with Black residents in L.A.

“Whites and the institutions they influence are rarely mentioned in the coverage of Black-Asian American conflict,” wrote Thornton and Shah. “They are most often characterized as innocent bystanders or victims of minority violence.”

It’s not that conflict within the two communities doesn't exist – it’s that the news relishes in stories of this nature, creating a narrative of never ending animosity and bitterness. The original intention of the Black-Asian conflict trope, and of the Model Minority Myth, is to “prove” that systemic racism against Black people doesn’t exist.

To begin disrupting this practice, “Media needs to redefine the nature of racial news, to go beyond the unusual and to include historical, economic, and social contexts and insight into the immediate situation,” according to Thornton and Shah.

NPR’s article isn’t the ideal example of how news should “redefine” reporting on race. But we did see a rare example of journalism that depicts nuanced relationships between and within communities of color.

There are very real tensions within the Black-Asian community, stemming from economic competition and prejudices. Asian Americans have seen anti-Blackness rear its ugly heads within our own families, especially after the murder of George Floyd. The backlash to the article shows that, because we lack the language to honestly discuss these tensions, we jump fearfully at anything that appears to expose potential rifts.

In order to forge a path toward sustaining racial solidarity, we can’t pretend these rifts don’t exist. When we as Asian Americans seek to have honest conversations about things like the historic exploitation of Black consumers or displacement of Black businesses, we can tell more nuanced stories about our two communities. We won’t hide or shy away from conflict, we certainly won’t sensationalize it, but we will take the power of narrative back.

For further reading:

Thornton & Shah | US news magazine images of black‐Asian American relationships, 1980–1992

Current | How journalists are challenging ideas of objectivity while empowering their communities

What do you think of NPR’s reporting on Michelle Wu’s election? Leave us a comment!

If you liked what you read, be sure to subscribe above and follow us on Twitter and Instagram @invisibleasians to stay updated on Politically Invisible Asians!