Like many other minorities, I’ve spent a great deal of my life looking for myself in the image of others. In TV shows, movies, books, and social media seeing characters or cultures with any vague relation to myself always impressed me. Although I would recognize the little tokenized aspects of my life such as in a Bollywood fusion dance number or the stereotypical Asian parents with too much academic fervor, that's all that it was, recognition, rarely reflection. Instead of seeing a reflection of myself, my story, and my cultural upbringing, the image spewed at me often resembled a distorted perception of who people perceived South Asians to be; it felt like looking into a broken mirror.

I felt this distortion once again as 21-year-old Harnaaz Sandhu was crowned Miss Universe 2021 while representing India. Many Indian Americans took their joy to social media to celebrate her win, with many influencers and social media accounts even calling it a recent win for Brown women. While I admire the effort she must’ve put into the competition and her ability to overcome generational barriers, I have to say I don’t see myself represented in a light skin Punjab woman born and raised in India as a dark-skinned Tamilian born in the Midwestern United States, but for those who do, that’s okay.

When representation is attempted by white creators the result is often cliché traits ascribed to brown skin. Yet the South Asian narratives spotlighted by our community usually consist of generalizations based on North Indian culture or wins by the most socially and politically powered members of our population. No matter who controls the narrative, why does South Asian storytelling often feel lackluster? There may not be just one answer, but the emergence of the South Asian “diaspora” identity poses an explanation to why the portrayal of our lives pales in comparison to the actual intricacy of our cultures.

The Diaspora Debate

Diaspora by Merriam Webster dictionary is defined as: people settled far from their ancestral homelands.

The South Asian diaspora refers to people with cultural ties to Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and the Maldives. Even though these countries collectively include roughly ¼ of the world’s population, they also contain thousands of different ethnic groups, languages, and histories. Even the concept of a South Asian diaspora is not nearly as recognized in these home countries as it is in the United States. The emergence in popularity of the term “South Asian” and similar terms like “Brown” and “Desi” became salient as these groups appeared as a prominent minority in white spaces and needed a common identity to define their relation to whiteness.

After 9/11, these labels became particularly relevant as the U.S. government launched its “war on terror” which led to the targeting of Brown people both domestically and abroad. The generations growing up in the 2000s built a common identity around “Brownness” to mobilize against hate crimes targeted at those with brown skin. Self-identifying as “South Asian” also helps distinguish South Asians from East Asians as many South Asians do not feel comfortable identifying with the term Asian American.

On the other hand, terms such as “Desi” have been criticized for primarily denoting North Indians, and the “South Asian” label, in general, has come under scrutiny for centering Indians. Academics and writers often view the diaspora as problematic because it promotes a homogenizing view of South Asians which leads to the further racialization of these communities. Lastly, these labels have been viewed as “opportunistic” and used as an excuse to manipulate representation politics which truly speaks to our current political atmosphere.

How Others Tell Our stories

Oftentimes it appears we are lumped together into the “South Asian” label for the ease of others, particularly white Americans, who desire to group, oppress, and stereotype South Asian people. This desire can be seen through the way in which white creators reduce South Asians to a conglomeration of monocultural stereotypes such as Ravi from Jessie, Baljeet from Phineas and Ferb, and Apu Nahasapeemapetilon from The Simpsons. Heavy discourse continues to surround these characters and their conformity to the nerdy, undesirable, and socially awkward image of South Asians.

But How Do We Tell Our Stories?

While we obviously cannot be held accountable for the stereotypes imposed on us, the way we tell South Asian stories often caters to white audiences, which erases our intercommunity complexity. We perpetuate a monolithic view or the illusion of some universal commonality between the South Asian diaspora. The forced generalization of such a large group of people has forced us to form a community based on artificial connections and causes.

Narratives that conform to the general “Brown” experience usually fare better than more nuanced stories. Although when we’re younger it is harder to identify it because we’re so pleased with receiving any representation at all. Looking back, someone I loved growing up, Lilly Singh often played into the monolithic view of the Brown community; Brown girls who lack social experience and awareness, caricatured strict immigrant parents, and of course the undying love of Kuch Kuch Hota Hai.

For the record, I grew up watching as much Shah Rukh Khan as the next Bollywood fanatic and can relate to some aspects of her comedy. I think the problem arises when we realize that this is the one type of Brown story that gets amplified when millions exist, likely due to its ability to appease white audiences as well. This narrative fits the image white people have of South Asians and therefore the jokes are easily comprehensible to them in a way that more narrow narratives wouldn't be. Are these bits and fragments used to portray our existence enough? When do these “harmless” jokes and exaggerations become conflated with the stereotypes already imposed on Brown people?

Aesthetics and Activism

To some extent over the past decade there has been an increasing awareness of how this portrayal of South Asians does more harm than good, but as South Asian has become an increasingly racialized and therefore political identity, we’ve had to grapple with what actually defined the “South Asian” identity, and the answer recently seems to be aesthetics and “activism.”

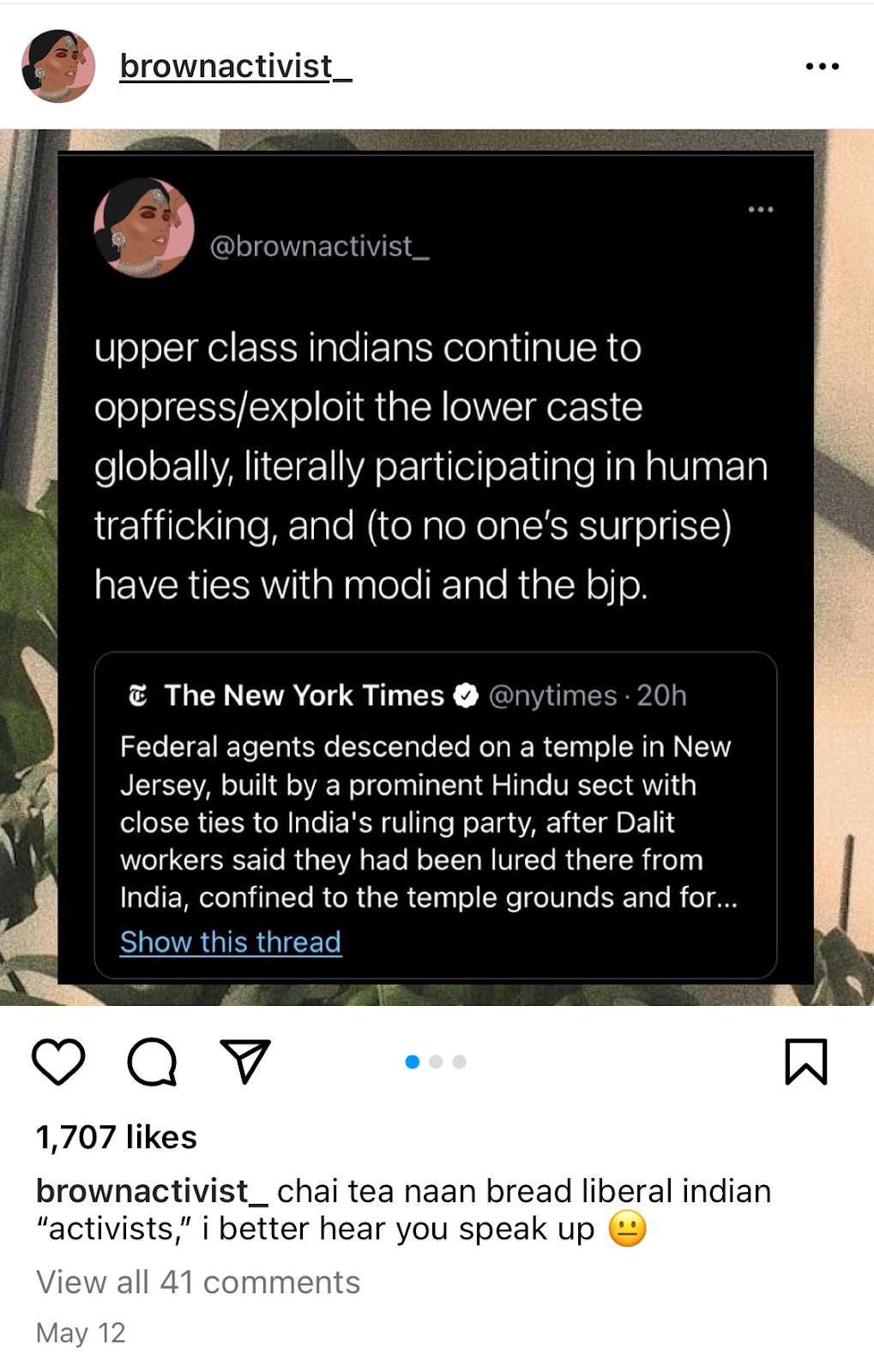

The sheer number of people under the diaspora suggests that activism would be an effective means of storytelling, instead, regurgitated narratives plague the South Asian “activist” community. I have heard more stories gaining traction of Brown people being told they “smell like curry” or were made fun of for their arm hair than ones of intracommunity patriarchy, Islamophobia, casteism, colorism, and homophobia. Both are unjust but the latter produces much more serious consequences. However, the former instances have a relation to whiteness and the audience of scrutiny is white allowing the Brown community to turn a blind eye to issues they may have to be held accountable for.

A plethora of social media presences who appeal to the broad diaspora through “aesthetics” fail to show up for larger issues. Well-known influencers Sruthi Jayadevan and Hamel Patel whose careers are built upon their infusion of Desi heritage into their image did not speak on the Kashmir crisis. It makes us wonder what the diaspora community is built on besides shallow identity markers. However, aesthetics are easily consumable hence their popularity, and pages that dare to speak on controversial issues rarely receive as much engagement.

The first two Instagram pages label themselves as “Brown”, but the one appealing to the typical Bollywood aesthetic associated with South Asian identity has received tenfold the number of likes.

But appeasing the diaspora does not stop at chai tea activists. Brown creators who have attempted to connect to their heritage through what some call “mango diaspora poetry ” have been labeled as ingenuine as well.

Controversial poet, Rupi Kaur, serves as the prime example of this type of poetry. This type of poetry often uses the mango as a symbol to convey a romanticized image of one’s home country. In an effort to convey the story and pain of immigrants, these poets often fall to an "exoticizing gaze" which dismisses the complexity of each country to appeal to the “diaspora.” She draws on the stories from lives she has not experienced causing her to be accused of superficiality.

It would be unfair to completely blame Rupi Kaur for contributing to this type of poetry. White audiences habitually support immigrant stories of trauma above everything else. “Trauma porn” is often the most sought-after commodity in South Asian stories. Hence the portrayal of many South Asian countries as underdeveloped and impoverished in Western media. Bottom line is that aesthetics and trauma porn garner attention in ways that authentic storytelling rarely does.

By attempting to represent all, we often end up representing none. The “diaspora” often hinges on the existence of shallow connections instead of a deep intercultural understanding of different groups and their dynamics. When we force ourselves beyond the diaspora, beyond the “Brown” or “Desi” labels, we may find ourselves tackling more pressing subjects.

Holding Ourselves Accountable

There are undeniable connections between us. Yet ignoring the fact that we speak different languages, practice different religions, have different relationships with our families and cultures, and come from different socio-economic backgrounds doesn’t bring us closer together. Engaging in the diaspora can be fun, it can give us a sense of belonging in a country where we are a minority. However, we must proceed with caution. We must hold ourselves accountable to seeing issues the diaspora does not through intersectional activism which pushes ourselves to defend communities that we are not directly a part of. We should attempt to boost underrepresented South Asian stories and be critical of what narratives we repeatedly pay attention to or we claim as a “win for all.” Aesthetics may be part of but not the forefront of our image; drinking Chai, watching Bollywood, and having strict parents is not what defines South Asianness. What defines us is truly individual, so let's ask ourselves what truly connects us to our heritage and one another?

Existing as an identifiable minority in America means that the diaspora identity will likely always exist, but we as a community should make sure we do not erase the complex interrelationships between us to accommodate our image in white spaces. Attempts to represent the diaspora simply come off as ingenuine because it is near impossible to represent such a large conglomerate of people without relying on artificial aesthetics and stereotypes.

“There is hope that the decade to come will bring more stories not just broadly about an amorphous “us,” but stories truly for us.”

— Kiran Misra

Identity politics and blind nationalism will not liberate us and ironically the only thing that will truly bring us together is acknowledging our differences. Brownness should be the beginning and not the endpoint of our narratives.

Finally, I have to acknowledge that I have primarily focused on the Indian community since as a Tamil American it is the community I have been able to personally encounter and continuously observe, yet much remains to be said on what other identities are continuously left out of the perceived South Asian identity.

So what are your thoughts on the diaspora debate?

Read more:

Asia Society | The Desi Diaspora | Asia Society

NBC | Brown, Desi, South Asian: Diaspora reflects on the terms that represent, erase them

South Asian Multidisciplinary Academic Journal | The Construction, Mobilization, and Limits of South Asianism in North America

The Washington Post | How did 9/11 change South Asian Americans' identities and politics?

Lit Hub | On the Complexity of Using the Mango as a Symbol in Diaspora Literature

This was such an insightful piece. Thank you for sharing.

Amazing analysis on the current discourse of how South Asians are depicted. Writer discusses the current state of how narrative storytelling is still monolithic in a celebrated “diverse” world, and the detriments of making minority stories more palatable. Vital points that our community needs to work even more diligently to lessen and remove. 10/10 compliments to the creator and master 👏🏼👏🏼