Ethnocentrism Against Cultural Foods

What is ethnocentrism, and how can it play into the racism that Asian diaspora face?

It can be funny how people can get so heated over whether pineapple belongs on pizza, or whether milk or cereal goes in the bowl first. “That’s disgusting,” people are so quick to say, jumping at the chance to wring hilarity out of being strongly opinionated over mundane topics.

It’s no longer funny, though, when people apply the same judgement towards food or practices from cultures that are not their own.

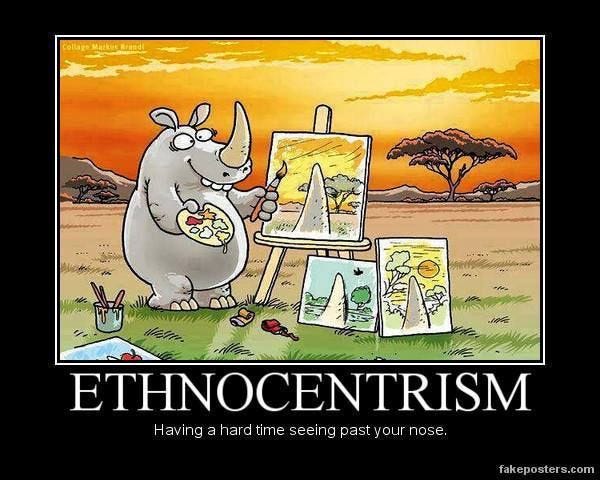

Ethnocentrism—the mistaken view that one’s own culture is the normal or superior culture, and others are evaluated in reference to it—is a term that I first encountered in an introductory anthropology class. Modern anthropologists (are supposed to) try to fight ethnocentrism with cultural relativism—seeking to understand each culture on its terms, rather than applying the terms of their (the anthropologist’s) own culture on the culture they are studying.

Ethnocentrism can start simply as judgement, but can exotify and alienate certain people in a cultural space, which can cause ignorance and hate. At worst, this belief can lead to violence against members of the exoticized community.

Ethnocentric Views of Asian Foods

For lunch every day up until the third grade, my working single mom used to pack me a Tupperware of leftovers from the previous nights’ dinner, usually something pan-fried on the wok.

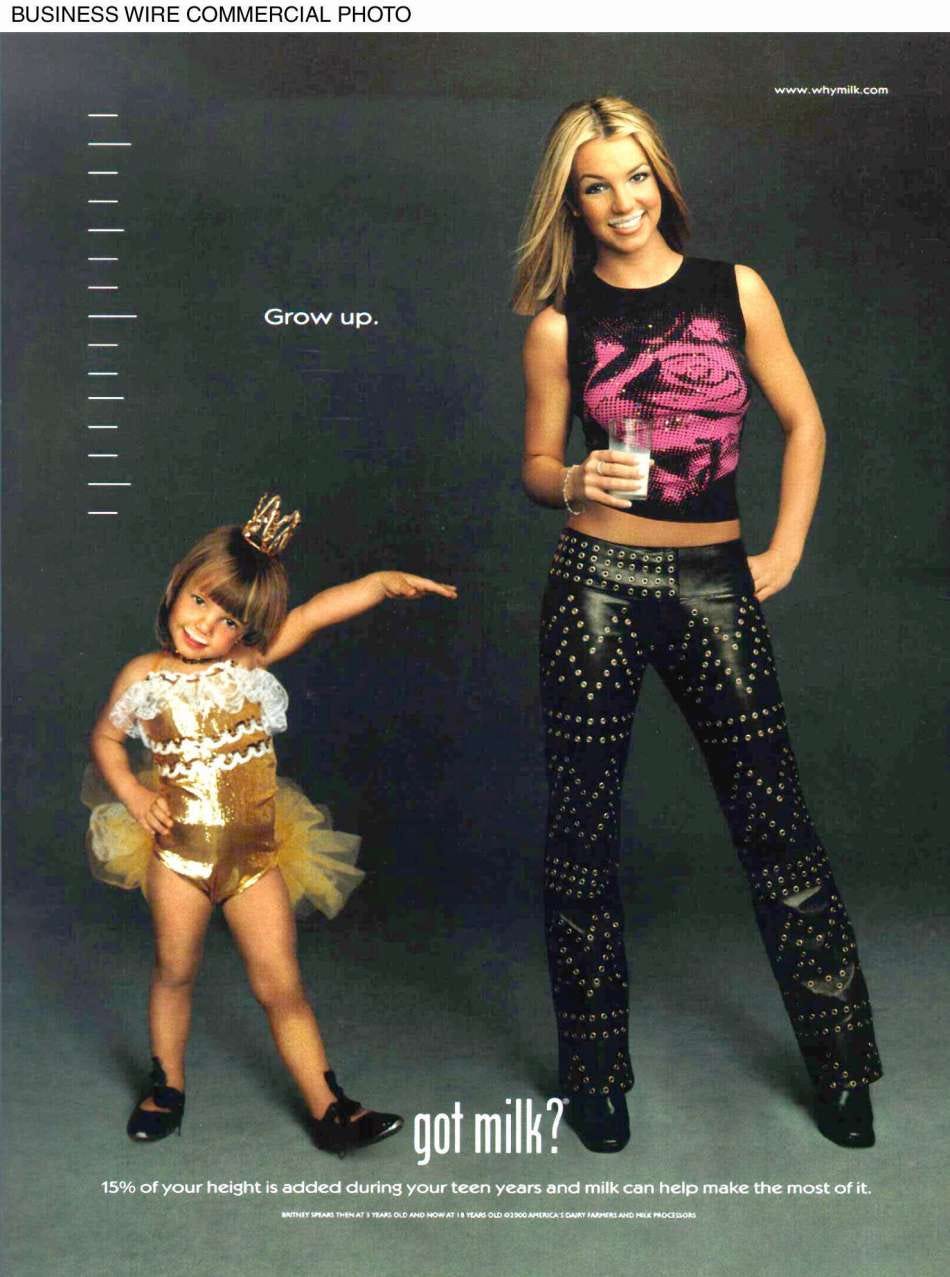

Instead, I longed to join my friends who lined up on the side of the cafeteria for twenty minutes for cardboard pizza and boxed chocolate milk. The people on the “Got Milk” posters pasted on the walls stared down at me with their milk mustaches, taunting.

Every time somebody told me my food or how I ate it was weird, I felt a wall coming between me and my peers. I found myself often burying the ugly feeling that came over me every time a friend told me my food was smelly and gross. I realized quickly that I didn’t want my family’s food to be what people thought about when they saw me, a part of my identity. From my peers, I learned to internalize racism against my own culture. And in the effort to fit in, at school, I started to distance myself from the foods I ate at home. I’m not alone in this experience either; it even has a name: the lunchbox moment. However trivial these microaggressions might seem, they define what types of food are “acceptable,” and by extension what cultures and people are “acceptable.”

Recently, James Corden’s “Spill Your Guts or Fill Your Guts” segment on his late night television show has come under fire when Kim Saira posted a Tiktok that pointed out its underlying racist tones.

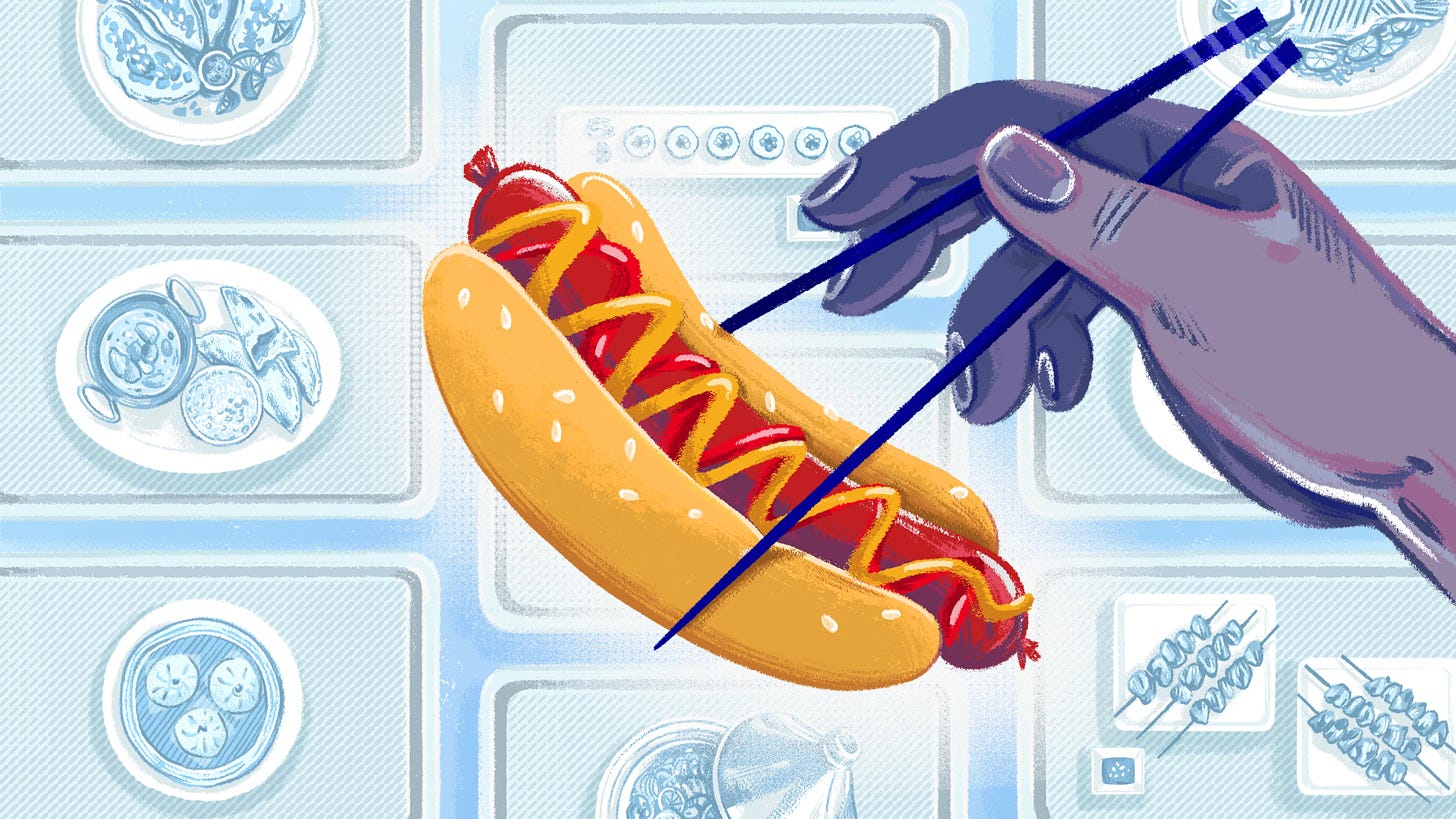

The segment opens with a shot of seemingly “disgusting” foods. Corden and the guest on the show then have to play a game where they answer difficult questions, or eat one of the dishes as a punishment. While the premise is seemingly harmless, Corden presents hot dog juice, shots of mayo and hot sauce alongside elements of Asian dishes.

When I first watched an episode of the show, a lot of what was supposed to strike me as disgusting didn’t evoke its intended effect. I quickly realized I wasn’t the target audience. The show has featured dishes or ingredients that have made appearances at my dinner table at home: 1000 year old egg, jellyfish, chicken feet, fish eyes, bird saliva, etc.

Corden and most of the guests on the segment are white. One of the first things that many guests immediately comment on is the odor, and the comments are vaguely reminiscent of the “lunchbox moment.” Whether or not the show intends to attack cultural dishes, it succeeds in not only alienating its Asian audience, but also perpetuating the notion that foods—and possibly by extension, people—from certain cultures are “disgusting.”

Due to fishy similarities between Asian dishes and the “disgusting” foods on the show, Corden has said that the segment would no longer be featuring Asian foods. However, it's a far cry from an apology.

The Dog Meat Comment

A student had asked if she eats dog meat, my high school Mandarin teacher told me when I stopped by her classroom after school.

I wasn’t shocked–and neither was she–at the familiar comment; many diaspora of various Asian groups in the States have gotten some variation of this comment. However, it was shocking that it was said so blatantly to a teacher’s face.

When you get this comment as a small indignant child, you might have protested vehemently: “I have a dog and I would never eat her!”

In your trying-to-fit-in phase, you might have laughed it off or even played into it, wanting so desperately to fit in that you take what you can get.

At some point, it just gets tiring to even acknowledge. As you attempt to divert the topic, just a fleeting thought might pass through your mind: Is this supposed to be funny?

Generally in Western society, the consumption of certain animals is accepted while the consumption of other kinds of animals is demonized. The application of this Western standard to other cultures is ethnocentric because it judges one culture through the standards of another. I want to preface this discussion by noting that personally, I don’t know a single Asian American (or anyone for that matter) that consumes dog meat. Also, in China, the country that most point to for being the largest consumer of dog meat, most of the population has never eaten it and there is shaky validity behind the reasons behind the existence of a dog meat festival there.

Despite the fact that the stereotype is largely false, unpacking it reveals the hypocritical and ethnocentric nature of the “dog meat comment.”

In the US and the West, most people will villainize dog meat trade and consumption, but don’t question the ethics of eating other livestock: cows, pigs, chickens, etc. Baby livestock are turned into food too. These animals are also notoriously subject to unhealthy and cruel conditions.

Yet, outside of vegan and vegetarian circles, Americans aren’t cast in an evil light for eating those animals. On the contrary, the consumption of animal products is promoted by the government and agricultural industry.

However, other cultures’ consumption of what Western countries perceive as another category of animals (i.e. pets) is seen as ghastly. This perception is ethnocentric because it places Western standards of which meats are “acceptable” to eat onto communities outside the West. Not only is this perception limiting, it is also harmful because it leads to the dehumanization of people in or adjacent to these communities (Asian diaspora, for instance). As we’ve seen throughout the past year, what is just a stereotype can become dangerous when it’s used to justify violence against Asian diaspora.

Portrayal of Asian Foods as Unhealthy

As discussed in a previous Politically Invisible Asians article, there is a negative stigma surrounding MSG, which is used to add umami flavor to many Asian dishes. This stigma arose from xenophobia rather than science.

The term “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome” falsely described a phenomenon that food seasoned with MSG, and especially from Chinese restaurants, would cause certain symptoms like headaches, dizziness, etc. This term was ethnocentric because it claims that food from Asian and Chinese restaurants was inherently less healthy than food from other restaurants.

Last year, the Merriam-Webster definition has since been updated due to this campaign, but the negative connotation surrounding MSG still remains.

Hot Water

When I’m at dim sum with my family, one of the first things they will ask is what tea to get for the table. Afterwards, they usually turn to me or a family member to ask if I, the only Gen-Z person at the table, if I want a glass of ice water.

The assumption that I might want to drink something different comes from the fact that most Americans don’t drink hot water, and I look Chinese American (because of my age and the way I’m dressed). I used to feel a certain degree of embarrassment or ostracization at being singled out, and would refuse the ice water.

Similarly, I’ll get weird stares and questions from my non-Asian friends when I drink hot water straight from the Zojirishi water boiler in my kitchen. Unconsciously, I sense slight judgement and feel that I need to defend something as trivial as what temperature the water I’m drinking is at.

These examples seem to be on such a trivial scale, but it points to how everyone is socialized with some degree of ethnocentrism within ourselves. It's important that people actively face and unlearn their own ethnocentric ideas. Even though I’ve felt forms of ethnocentric judgement from both white people and people in the Asian community, more work needs to be done on the former’s side. It ultimately comes down to power: while ethnocentrism from people in the Asian community can simply be judgement, ethnocentrism from white people has the power to put Asian diaspora into danger. Even though we are starting to come out from the pandemic, the racism and violence against Asian people has continued to persist, which makes it that much more necessary to unlearn ethnocentrism.

I’d love to hear from you all! Leave a comment or question below. Thank you!

To further decolonize our minds:

Seedtolife | Ethnocentrism and Food

Taft McConkie | Ethnocentrism, or Group Pride

Eater | The Limits of the Lunchbox Moment

Taste Cooking | Do You Eat Dog?

NPR | Asian Americans Feel the Bite of Prejudice During the COVID-19 Pandemic

If you liked what you read, be sure to subscribe above and follow us on Twitter and Instagram @invisibleasians to stay updated on Politically Invisible Asians!